Latest News

Upper Valley egg hunts and Easter events 2025

Upper Valley egg hunts and Easter events 2025

Alerts to crime victims in Vermont are full of flaws

Alerts to crime victims in Vermont are full of flaws

Upper Valley community nurses seek to help people stay safe at home

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION — Joan Ponzoni wasn’t feeling well when she arrived at the Bugbee Senior Center one day in January.

High egg prices drive interest in raising backyard flocks

WEST LEBANON — On Thursday, the first of a seasonal series of monthly chick delivery days at West Lebanon Feed & Supply, a cacophony of chirps greeted customers as they stopped in to pick up their orders.

Most Read

Hartford Selectboard mulls closing road off Sykes Mountain Ave

Hartford Selectboard mulls closing road off Sykes Mountain Ave

After a year of looking, White River Junction couple finds new home

After a year of looking, White River Junction couple finds new home

Upper Valley beekeepers assess winter losses

Upper Valley beekeepers assess winter losses

Editors Picks

New arts school offers alternative in downtown Lebanon

New arts school offers alternative in downtown Lebanon

Upper Valley fire departments prepare as wildfire season lengthens

Upper Valley fire departments prepare as wildfire season lengthens

Editorial: Jeanne Shaheen blazed a trail in politics

Editorial: Jeanne Shaheen blazed a trail in politics

Kenyon: Dartmouth brings Trump ally into Beilock’s inner circle

Kenyon: Dartmouth brings Trump ally into Beilock’s inner circle

Sports

Men’s lacrosse: Big Green finally holding serve in Ivy League

HANOVER – Spring weekends in Hanover mean an influx of late-model luxury vehicles rolling into the Scully-Fahey Field parking lot, their occupants headed to watch the Dartmouth College men’s lacrosse team tilt at the collective windmill of Ivy League opposition.

New Hampshire lawmakers target another source of PFAS: waxes used by skiers and snowboarders

New Hampshire lawmakers target another source of PFAS: waxes used by skiers and snowboarders

Whaleback seeks support to repair and replace ski lift

Whaleback seeks support to repair and replace ski lift

Windsor outlasts Oxbow to win DIII hoops title

Windsor outlasts Oxbow to win DIII hoops title

Opinion

Column: Federal funding for medical research puts America first

When my grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in the mid-1990s, there were few options for therapies and treatments. As her disease progressed over the next decade, there was little that could be done until she died in 2004. I was still in elementary school when she faced this disease, which has unfortunately left me with few memories of her where she was not ill or bed-ridden.

Editorial: MLB resumes all-American pursuit of new billions

Editorial: MLB resumes all-American pursuit of new billions

Editorial: NH police put mission aside to pursue immigrants

Editorial: NH police put mission aside to pursue immigrants

Column: Lebanon trades one annoyance for another

Column: Lebanon trades one annoyance for another

Editorial: If politicians want respect they’d better earn it

Editorial: If politicians want respect they’d better earn it

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Photos

Burning passion

Martin Pastor splits wood before bringing it into his home in Hanover on Thursday. Pastor burns about six cords of wood per winter, using his fireplace and wood stove. Pastor often cooks over the fireplace, saying, “Since I was a Boy Scout, it is something I like to do.” He enjoys cooking venison after having good luck during hunting season.

Time for a change

Time for a change

Cat walk

Cat walk

Blowing the blaze

Blowing the blaze

Perfecting her pitch

Perfecting her pitch

Arts & Life

Upper Valley beekeepers assess winter losses

WINDSOR — Last year, beekeeper Brian Jasinski reached a new milestone in his business by surpassing 300 colonies of honeybees. He hoped hitting that mark would allow him to sell new products this spring.

Art Notes: ‘If you love ‘Messiah,’ you’ll love this piece’

Art Notes: ‘If you love ‘Messiah,’ you’ll love this piece’

Farmer-led project gets grant to recycle agricultural plastics

Farmer-led project gets grant to recycle agricultural plastics

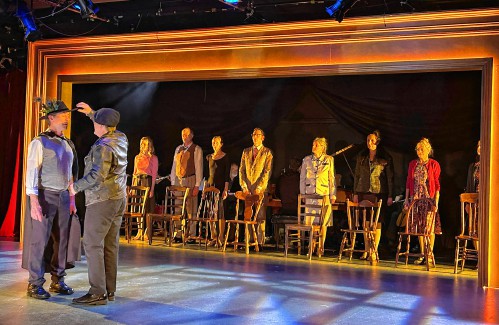

Art Notes: We the People’s latest show offers hopeful message

Art Notes: We the People’s latest show offers hopeful message

Halls Lake in Newbury earns Gold Lake Wise Award

Halls Lake in Newbury earns Gold Lake Wise Award

Obituaries

Judy Hill

Judy Hill

Windsor, VT - Judy L. Hill, age 66, passed Sunday, March 16, 2025. A graveside service will be held in Child's Cemetery in Cornish, NH on April 12, 2025, at 1pm. A celebration of her life will follow in the Cornish Town Hall. ... remainder of obit for Judy Hill

Marilyn M. Gates

Marilyn M. Gates

White River Junction, VT - Marilyn M. Gates, 93, passed away peacefully on Saturday, March 29, 2025, at Cedar Hill Health Care Center in Windsor, VT. She was born on July 2, 1931, in Hanover, NH to Percy N. and Louise (Roberts) Courtema... remainder of obit for Marilyn M. Gates

Deborah Anne Garretson

Deborah Anne Garretson

West Lebanon, NH - Deborah Anne Garretson died quietly on March 2, 2025, at the Jack Byrne Center for Palliative & Hospice Care of complications of stage 4 lung cancer. She had just celebrated her 80th birthday. She was held lovingly by... remainder of obit for Deborah Anne Garretson

Gordon E. Bagley Jr.

Gordon E. Bagley Jr.

Lebanon, NH - Gordon E. Bagley, Jr., 86, peacefully passed away at home on Thursday, March 27, 2025, with his loving family by his side. Gordon was born in Lebanon on January 30, 1939, son of Gordon and Marie (Sanville) Bagley. He grad... remainder of obit for Gordon E. Bagley Jr.

Still at odds over motel program, Senate sends another spending bill to Phil Scott

Still at odds over motel program, Senate sends another spending bill to Phil Scott

Editorial: Time is running out for American democracy

Editorial: Time is running out for American democracy

Local group expected to acquire Burke Mountain ski resort

Local group expected to acquire Burke Mountain ski resort

Girls hockey: Hanover dominates Oyster River-Portsmouth, repeats at state champ

Girls hockey: Hanover dominates Oyster River-Portsmouth, repeats at state champ