A Look Back: Catamount Brewing remembered as ‘a pioneering kind of venture’

| Published: 04-05-2025 2:01 PM |

It was going to become “the Ben and Jerry’s of beer” and as the concept took shape it generated a lot of buzz in the Upper Valley some 40 years ago.

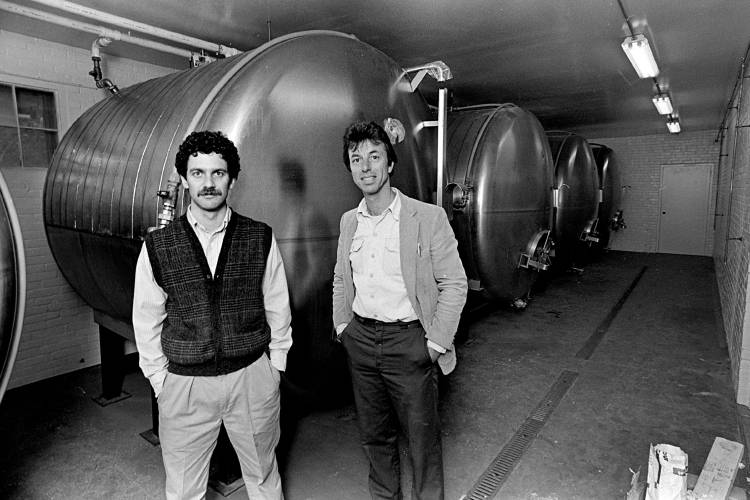

Catamount Brewing Co. was Vermont’s first indigenous brewer since before Prohibition, a pioneer in the nascent New England craft brewing craze and, most exciting of all, it would be located in downtown White River Junction.

Catamount went on to develop a cult-like following among malt beverage connoisseurs over parts of New England that kept its bottling line humming for a decade before ownership decisions to ratchet the brand up with a new high-tech brewery in Windsor eventually led to the enterprise abruptly toppling and the label going virtually extinct.

Vestiges of Catamount’s short life are sometimes spotted on an ancient T-shirt or on pint glasses bearing the distinctive feline logo now tucked away in cupboards or traded at yard sales. The successor brewery in Windsor, Harpoon, makes a nostalgia batch from time to time using original Catamount recipes.

The aim of the founders was to create a premium quality product similar to that of imported European brews that dominated the high end of the U.S. beer market. They planned to hit a price point below the imports and above that of industrial-scale brewers like Miller and Budweiser. Founders Alan Davis, Steve Mason and Stephen Israel took their idea for a new brewery in Vermont to state officials in Montpelier and connected with Patricia Moulton, head of the Green Mountain Industrial Development Corp.

It was Moulton who declared the proposed brewery would be akin to Vermont’s ice cream sensation Ben and Jerry’s, “only better, much better.” She helped line up financing and found a location for the business, the vacant Swift & Co. meat distribution plant on South Main Street in White River Junction.

Mason took on the title of brewmaster and promised that the small size of the brewery would enable production of a beer with “fresher and more distinct taste” than that of mass market products. Initially, Catamount set out to produce the equivalent of 1,600 six packs a week, but it would take well more than a year to get brewing and packaging equipment set up and product testing completed. At the time, there were few U.S. sources of brewing and packaging equipment scaled to operations of Catamount’s size.

Mason was quoted at the time saying, “It’s a pioneering kind of venture. A book hasn’t been written on it. It’s not like starting a variety store where you can talk to a dozen people in the area who have done that.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

The well-used bottling equipment came with a story that it once was in the background of a set in the TV sitcom “Laverne and Shirley.”

In late January 1987, the first shipment of Catamount entered the Vermont beer supply chain, and retailers soon were being besieged with buyers looking for the new product. It quickly became a much-sought-after commodity all over the range of its namesake, a mountain lion that once roamed Vermont and western New Hampshire. A private grand opening ceremony attracted Gov. Madeleine Kunin and other dignitaries. Catamount Gold and Catamount Amber were off on a sales surge despite hardly any investment in traditional marketing strategies.

The Gold variety was described as full-bodied with a distinctive hops aroma, while the Amber was likened to a traditional British ale. Both products were unpasteurized to assure freshness, Mason said.

At the time the only other unpasteurized beer on the market was Coors. By late 1987, Davis was proclaiming that sales had easily exceeded targets, and grocers were complaining that Catamount was selling out the same day shipments came in.

Strong demand would continued, leading to widening of the marketing area to the rest of New Hampshire and into southern New England. The company was producing about 6,000 barrels — 186,000 gallons — per year and the broader sales territory meant chronic undersupply for retailers, bars and restaurants.

In late 1990, a $400,000 addition was constructed on the brewery building to house new fermentation and conditioning tanks that allowed Catamount to boost production to 10,000 barrels per year. Mason sounded an optimistic view: “We can’t keep up with demand in our existing territory, so the first priority of our expanded capacity is to meet present demand and, secondly, to provide opportunity for new products and slow expansion of distribution into new markets.”

The brewery became a popular spot for tours and a training ground for aspiring young brewers, some of whom, to Catamount’s later detriment, went off to join or start competitor beer enterprises. Investors jumped onto the Catamount team, bringing in cash through a private sale of stock and the company took on debt with loans from the Vermont Industrial Development Authority and a local bank guaranteed by the U.S. Small Business Administration.

Media accounts from 1993 reported Catamount turning profits the three latest years, and one gushing account said the three biggest craft brewing operations in Vermont — Catamount, Mountain Brewing (Long Trail) in Bridgewater and Middlebury’s Otter Creek — were “tapping into big profits.”

But some concerns were showing up on the horizon:

Competition was ramping up, and not just among the Big Three Vermont craft brewers. New entities were popping up all over the Northeast. Some traded on their geographic identity, others with cutesy names. New players like Sam Adams were in with the resources to carry out sophisticated marketing campaigns to win attention and new customers.

And the big guys like Anheuser-Busch and Miller who had spent decades eliminating smaller regional brands like Ballantine and Rheingold were fighting off any reduction in their market shares, even if only a tiny fraction of 1 percent. They had an arsenal of promotional resources, price gimmicks and brand extensions — new labels designed to look like craft brewery products — to throw into the fray.

Rising prices were brought on by increased state and federal taxes, higher transportation expenses and soaring costs throughout the entire brewing and distribution chain.

As prices went up, consumers reacted by cutting back on their beer budgets, especially for the higher-end products. Bars particularly saw margins on draft and bottled products shrink.

The operator of a busy Hanover restaurant said prices of imported beers in 1993 had shot up so much it was impossible to offer bottled products and thus he had shifted to mostly draft mugs at a lower price and less profit.

Changing demographics presented a mixed picture. The 21-34 age group, prime years for beer drinkers, was slowly contracting, while expansion of the population of older drinkers was helping with sales of higher-priced, fuller tasting imported and domestic beers. But the older cohort’s consumption wasn’t enough to offset the younger generation’s decline.

Social standards were changing. The volume of beer (and all alcohol) consumption per person was declining, pushed along by reduction of the limit of blood alcohol from .10 to .08 for motor vehicle operation.

Catamount forged ahead with marketing into southern New England and New York City, and continued doing small amounts of contract brewing — making products for other companies who used their own brand identities.

But management, which included the voices of outside investors, was looking to expand distribution and exploit the continuing strong demand in its established sales territory. That led to a decision to build an entirely new brewery capable of increasing the company’s capacity to the range of 100,000 gallons annually, a nearly five-fold boost. The White River Junction location was too cramped for such a facility, so the focus shifted to the Carney industrial park, 12 miles south in Windsor.

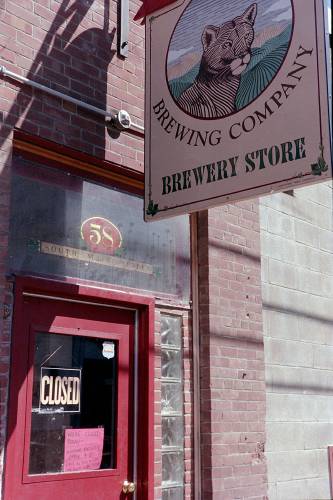

Construction began in 1996; Gov. Howard Dean snipped the ribbon at an opening ceremony in July 1997, and the last Catamount beer was bottled in White River Junction in May 1998. Many in the Junction were miffed that Catamount pulled out after the town of Hartford had helped with the finances in its early years, and mourned the loss of the estimated 15,000 visitors who toured the South Main Street facility annually. Dean called Catamount “an extraordinarily successful Vermont company.” Other public figures fell all over themselves praising the company and its shiny new Windsor brewery.

But astonishingly, in less than two years, Chittenden Bank of Burlington foreclosed on the company’s loans and took possession of its assets, including its building and equipment, which some estimated had a value of $5 million before the collapse. Also swept away were the jobs of 45 Catamount employees.

What went wrong was the topic of discussion in Windsor and beyond for years. Some people blamed bad advice from out-of-town consultants. Others said that after building the new facility and taking on the accompanying debt service there wasn’t enough money available to mount the aggressive marketing program needed as the craft beer business was becoming a tough, dog-eat-dog enterprise. Some said owners should have just stayed with the White River Junction model and not messed with its success.

Chittenden Bank shopped the asset package for two months before announcing the Boston-based Mass Bay Brewing Co., better known as Harpoon Brewing, had made an acceptable offer for the entire Windsor facility, a deal observers said at the time was for 20 cents on the dollar of value.

Now, a quarter century later, Harpoon has made a thriving enterprise out of the Windsor brewery and become an aggressive player in the rapid consolidation of the craft brewing industry in New England, including acquiring old Catamount rivals Long Trail and Otter Creek. Recently it formed a new umbrella company called Barrel One Collective that has taken in New Hampshire’s largest craft brewer, Smuttynose, and has 14 different beer brands produced at locations in New England and New York.

Steve Taylor has been an occasional contributor to the Valley News for many years. He lives in Meriden.

Hartford man dies while incarcerated

Hartford man dies while incarcerated  Hartford hires its first housing and development specialist

Hartford hires its first housing and development specialist So far exempt from tariffs, maple industry still feels their effects

So far exempt from tariffs, maple industry still feels their effects A New Hampshire ski resort bets on tech to compete with industry giants

A New Hampshire ski resort bets on tech to compete with industry giants