Upper Valley stove manufacturer hurt by tariffs, end of tax breaks

New Hampshire’s only manufacturer of wood stoves says it is being buffeted by costs and confusion from two different directions — tariffs and taxes — that will hurt sales and may lead to layoffs.

Royalton bridge replacement plan won’t include temporary span

ROYALTON — Despite the frustration of some residents, the Selectboard voted 3-2 last week to proceed with construction of a permanent span at Fox Stand Bridge, also known as Royalton Hill Bridge.

Most Read

Head-on crash in Hartland leaves one dead

Head-on crash in Hartland leaves one dead

Newport property maintenance firm closes amid embezzlement allegations

Newport property maintenance firm closes amid embezzlement allegations

With neo-Nazi rally in Concord, extremism and hate are on the rise in New Hampshire

With neo-Nazi rally in Concord, extremism and hate are on the rise in New Hampshire

A Life: Marie Doyle ‘was just so kind all the time’

A Life: Marie Doyle ‘was just so kind all the time’

Editors Picks

Woodstock, Windsor schools join collaboration that aims to improve special education and save costs

Woodstock, Windsor schools join collaboration that aims to improve special education and save costs

Tai chi and chair yoga help seniors stay active and social

Tai chi and chair yoga help seniors stay active and social

Editorial: NH Legislature shows disregard for child welfare

Editorial: NH Legislature shows disregard for child welfare

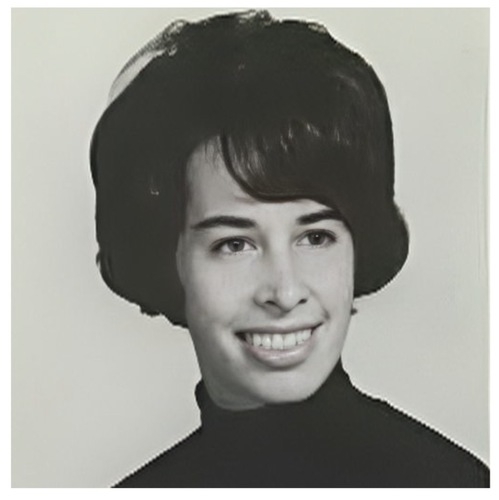

A Life: Kathy Hoyt was a ‘force in Vermont politics for years’

A Life: Kathy Hoyt was a ‘force in Vermont politics for years’

Sports

Test shows elevated level of E. coli at Canaan Street Lake beach

By CLARE SHANAHAN

Hiking: Plainfield native conquers Long Trail in record time

Hiking: Plainfield native conquers Long Trail in record time

Over Easy: Too hot, too high, too much

Over Easy: Too hot, too high, too much

Opinion

Editorial: NH betrays victims of YDC abuse

While the MAGA-verse is all atwitter about the Epstein sex trafficking files, its New Hampshire wing is further victimizing hundreds of people who suffered horrendous sexual and physical abuse while in state custody as children. Republicans in the Legislature, Gov. Kelly Ayotte and Attorney General John Formella are all implicated. This is unconscionable, at least to anyone who has a conscience.

Editorial: Questions for warm weather consideration

Editorial: Questions for warm weather consideration

Editorial: Grafton County officials' change of party raises questions

Editorial: Grafton County officials' change of party raises questions

Editorial: An education ruling that NH will disobey, again

Editorial: An education ruling that NH will disobey, again

Editorial: Shelter project shows healthy approach to housing crisis

Editorial: Shelter project shows healthy approach to housing crisis

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Photos

Teamwork in North Hartland

NORTH HARTLAND — Phoenix Cook, left, of Hartland, and Emily Pritchard, of South Royalton, react to the damaged camper tire they had just taken off Cook’s fifth-wheel camper.

Plainfield’s profitable partners

Plainfield’s profitable partners

Ready to roll in Hartford

Ready to roll in Hartford

Parking lot play time

Parking lot play time

Taking their dog for a swim in Mascoma Lake

Taking their dog for a swim in Mascoma Lake

Arts & Life

Handmade harp in Lebanon

LEBANON — Stephen Ryan, of Springfield, N.H., carries his daughter Joanna’s Paraguayan harp back to their vehicle after a lesson at the Upper Valley Music Center in downtown Lebanon on Friday.

Abenaki and Indigenous Peoples Honoring Day returns to Lyman Point Park

Abenaki and Indigenous Peoples Honoring Day returns to Lyman Point Park

Art Notes: ‘The Cottage’ brings farcical fun to New London Barn Playhouse

Art Notes: ‘The Cottage’ brings farcical fun to New London Barn Playhouse

Obituaries

Raymond Merrihew

Raymond Merrihew

Lebanon, NH - Raymond G. Merrihew, 83, of Lebanon, NH, passed away on August 17, 2025, at the VA Medical Center in White River Junction, VT. Ray was born in Lebanon, NH, to Thomas Merrihew and Ruth Strong, and graduated from Lebanon Hi... remainder of obit for Raymond Merrihew

Janet Aronson

Janet Aronson

Hanover, NH - JANET ARONSON: She passed away with her daughters at her side on Wednesday, August 20, 2025. Loving mother of Leah Matthew (Michael Matthew) and Lynn Garfinkel (Patrick Williams). Cherished daughter of the late Harry and D... remainder of obit for Janet Aronson

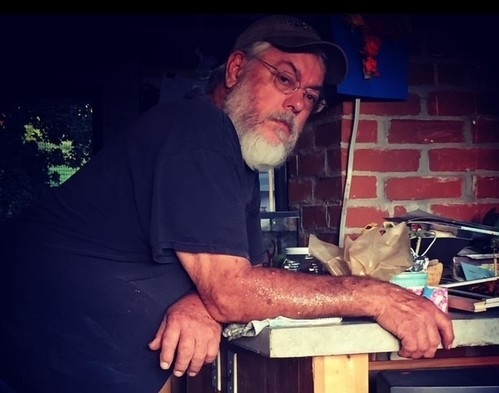

Ervin E. Needham

Ervin E. Needham

South Strafford, VT - Ervin Edward "Buster" Needham, 76 of South Stafford, passed away on August 21, 2025 at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center. Born on May 4, 1949 to Melvin Edward and Maude Abigail Russell Whitaker Needham. He was... remainder of obit for Ervin E. Needham

Kenneth David Parmenter

Kenneth David Parmenter

Bradenton, FL - Kenneth David Parmenter, 62, of Bradenton, FL, passed away peacefully on August 12, 2025, surrounded by his loving family, following complications from diabetes. Born in Worcester, MA, Ken was the son of Phillip Parment... remainder of obit for Kenneth David Parmenter

Water conservation measures in place for Newbury residents

Water conservation measures in place for Newbury residents

Claremont plans $1.3 million upgrade for Broad Street sidewalks and crossings

Claremont plans $1.3 million upgrade for Broad Street sidewalks and crossings

Police: Canaan man found dead with stab wound

Police: Canaan man found dead with stab wound

‘Who the hell are we as a state?’: John Broderick says new NH law guts, politicizes fund for youth detention center abuse victims

‘Who the hell are we as a state?’: John Broderick says new NH law guts, politicizes fund for youth detention center abuse victims

NH teen pleads guilty to 2022 triple murder of sister-in-law and two nephews

NH teen pleads guilty to 2022 triple murder of sister-in-law and two nephews

Editorial: Vermont should encourage local education reforms

Editorial: Vermont should encourage local education reforms

A Q&A with New Hampshire’s state epidemiologist, Dr. Benjamin Chan

A Q&A with New Hampshire’s state epidemiologist, Dr. Benjamin Chan

Students overcome challenges to earn diplomas from Vermont Adult Learning

Students overcome challenges to earn diplomas from Vermont Adult Learning

Rugby club in Upper Valley unites diverse group through sport and camaraderie

Rugby club in Upper Valley unites diverse group through sport and camaraderie Concord City Council votes to buy rail corridor with a ”heavy heart,’ threatening local rail bike business

Concord City Council votes to buy rail corridor with a ”heavy heart,’ threatening local rail bike business ‘This isn’t really a home’: As some unhoused Vermonters turn to sleeping in vehicles, advocates push for long-term solutions

‘This isn’t really a home’: As some unhoused Vermonters turn to sleeping in vehicles, advocates push for long-term solutions Brook trout populations spike after Vermont program adds wood to streams

Brook trout populations spike after Vermont program adds wood to streams