Hartford Redemption struggles to keep employees in what owner fears is a dying trade

| Published: 12-28-2022 10:44 AM |

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION — A co-owner of Hartford Redemption, the only certified can and bottle redemption center in the White River Junction area, said the center’s future could be in jeopardy due to ongoing staffing challenges.

Hartford Redemption, which leases space from the Hartford Transfer Station on North Hartland Road, has been a convenient drop-off site for area residents to bring redeemable beverage containers and collect the deposit.

Last week, Jacob Trombley, co-owner of Hartford Redemption, announced on Facebook that the center would have to “temporarily close for the month of January and possibly February” due to the lack of a full-time employee to run the facility.

Fortunately for Trombley and Hartford-area residents, a new employee was hired two days later, allowing the redemption center to remain open.

But despite solving the present crisis, Trombley said that recruiting and retaining staff has been a persistent problem largely due to what redemption centers can pay.

“I would love to keep good help,” Trombley said. “But there is a ceiling to what I can pay my workers.”

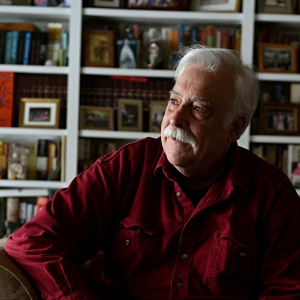

Trombley and his wife, Kim, own five redemption centers in Vermont, in Hartford, Springfield, Bradford, Hinesburg and Vergennes.

Trombley learned the business through his father, who owned and operated a certified redemption center in Vergennes for 35 years.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

As spring skiing season winds down, one NH ski area plans to spin its lift until May

As spring skiing season winds down, one NH ski area plans to spin its lift until May

Newbury,Vt., man who killed daughter ruled to be ‘not guilty by reason of insanity’

Newbury,Vt., man who killed daughter ruled to be ‘not guilty by reason of insanity’

Kenyon: The true cost of lawsuit for Dartmouth Health

Kenyon: The true cost of lawsuit for Dartmouth Health

Editorial: Free speech detentions reach into Upper Valley

Editorial: Free speech detentions reach into Upper Valley

Protesters rally in Lebanon and elsewhere across the country

Protesters rally in Lebanon and elsewhere across the country

ECFiber and operating company trade legal blows as contract renewal talks break down

ECFiber and operating company trade legal blows as contract renewal talks break down

Redemption centers are not highly profitable businesses in Vermont, Trombley said. Many of the state’s centers are located within grocery or liquor stores, which provide redemption services as a supplement to their main business.

“The only way we can make more money in redemption is to increase our volume (of containers),” Trombley said, explaining their ownership of five facilities.

Under Vermont’s redemption law, known as the “bottle bill,” the redemption center is paid by the beverage distribution companies for the cans and bottles it collects from consumers. The redemption center pays customers a rate of 5 cents per redeemable beverage container, such as beer cans or soda bottles purchased in Vermont, or 15 cents for certain liquor bottles.

When the containers are sent back to the distributors, the redemption center is paid back for the 5 cent deposit payout, plus an additional handling fee of 3.5 to 4 cents per container.

This handling fee represents the redemption center’s main profit line.

But Vermont’s handling fee rate was set in 1972, when the bottle bill was enacted, according to Trombley, and the state hasn’t adjusted the rate since.

Ideally, Trombley said he would like to have one to two employees in Hartford, one full-time and one part-time, and possibly a third employee during the spring and summer when business peaks.

But in recent months the center has struggled to maintain a full-time employee.

Trombley had to fire one employee for stealing from the cash register, he said. Another hire showed up for only two days.

More recently, “a couple of weeks ago,” Trombley found a Hartford center employee “slumped over inside his car” from what appeared to be a state of intoxication.

The full-time position at Hartford Redemption pays $15 an hour and after one year of employment includes one week of paid vacation, paid federal holidays and paid sick time, Trombley said. Part-time employees make minimum wage, which in Vermont is $13.18 an hour.

Employees also receive tips from some customers.

Dan Loskutoff, of Wilder, who redeemed bottles and cans on Tuesday with his wife Sue, said he frequently tips the employees on his visits.

“I am sympathetic to the service workers, so tipping is just a little thing one can do to help,” Loskutoff said.

The Loskutoffs said they donate the money from redeeming containers to charity.

Sharon resident “M” McGuire, who declined to provide her first name, said she typically redeems her cans and bottles at the Hartford center when she takes her recycling to the transfer station.

The center’s location and proximity to the transfer station makes it the most “accommodating” for McGuire, who said her next closest redemption center is M&M Beverage in Randolph, a liquor store that also provides redemption services.

Trombley, who had operated Hartford Redemption during the absence of a full-time employee, said the center’s future sustainability hinges on staffing. Trombley lives in Vergennes, which is approximately 75 miles and a 90-minute to two-hour drive from White River Junction. In addition, the time Trombley must spend at one center keeps him from assisting at his other facilities.

Springfield Redemption is the largest and busiest of the Trombleys’ centers, redeeming approximately 6 million to 7 million containers per year and requires a staff of three to four employees to operate.

Hartford Redemption redeems between 3 million to 4 million containers per year, Trombley said.

But without change at the state level to the bottle bill, redemption centers in Vermont are “a dying business,” according to Trombley.

“Most people love redemption,” he said. “But it’s becoming more and more inconvenient.”

Without the White River Junction center, the next closest certified center to Hartford would be in Ascutney, 20 miles away.

Finding a certified center in Vermont can also be difficult. An online list of centers, maintained by the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, was last updated in November 2021 and many of the listed facilities are no longer in operation.

Woodstock Beverage, a liquor store in Woodstock, has not provided redemption services since 2018, an employee told the Valley News.

Some businesses, such as supermarkets, provide self-service redemption machines, though Trombley noted that they can be inaccurate. These machines are also less efficient because they are more prone to accepting contaminated containers, or bottles or cans that are unclean or contain food residue or other waste. Though some contaminated containers, particularly aluminum cans, may still have value as recyclables though a number of containers wind up going into the general waste stream.

Patrick Adrian can be reached at padrian@vnews.com or 603-727-3216.

]]>

On the trail: Gov. Ayotte says she delivered on her promises in her 100 days in office. Not everyone agrees

On the trail: Gov. Ayotte says she delivered on her promises in her 100 days in office. Not everyone agrees Windsor snow globe business fears Trump tariffs

Windsor snow globe business fears Trump tariffs Fill ’er up: New Hampshire considers allowing patrons to pour their own alcohol

Fill ’er up: New Hampshire considers allowing patrons to pour their own alcohol  School Notes: Red Sox honor longtime Thetford Academy educator Ted Peters

School Notes: Red Sox honor longtime Thetford Academy educator Ted Peters