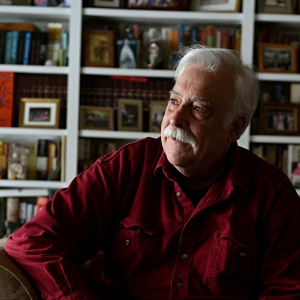

Kenyon: Hanover fights public scrutiny

Jim Kenyon. Copyright (c) Valley News. May not be reprinted or used online without permission. Send requests to permission@vnews.com.

|

Published: 09-20-2024 8:31 PM

Modified: 09-22-2024 6:48 PM |

Delay, delay, delay. The time-tested legal strategy is a sneaky way to keep the public from gaining access to police information that under New Hampshire law should be easily available to anyone who asks for it.

Hanover officials and their attorney must have known from the beginning that trying to hide basic police records from public purview could eventually catch up with them.

But I guess they figured they owed it to Dartmouth to hold out as long as possible.

In a town where Dartmouth reigns supreme (being a large taxpayer and the economic engine has perks), the fewer details out in the open about what led to the arrests of two students last October, the better for the college.

In the early morning hours of Oct. 28, Kevin Engel and Roan Wade were hauled away in handcuffs for refusing to leave a tent set up on the lawn in front of Dartmouth President Sian Leah Beilock’s office. The pro-Palestinian student-activists were protesting, among other things, the college’s refusal to divest its $8 billion endowment from companies tied to the Israeli military.

It took nine months — and a judge ruling twice against the town — before Hanover made the arrest records public this week.

The town rang up nearly $9,000 in legal fees to keep the arrest reports a secret. The town’s attorney, Matthew Burrows, of Gallagher, Callahan and Gartrell, in Concord, billed at $245 an hour.

In November, I asked Hanover Police Chief Charlie Dennis for the records. I figured it wouldn’t take long. Other Upper Valley police departments, including neighboring Lebanon, routinely release arrest reports within days, if not hours, of a request.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

As spring skiing season winds down, one NH ski area plans to spin its lift until May

As spring skiing season winds down, one NH ski area plans to spin its lift until May

Newbury,Vt., man who killed daughter ruled to be ‘not guilty by reason of insanity’

Newbury,Vt., man who killed daughter ruled to be ‘not guilty by reason of insanity’

Kenyon: The true cost of lawsuit for Dartmouth Health

Kenyon: The true cost of lawsuit for Dartmouth Health

Editorial: Free speech detentions reach into Upper Valley

Editorial: Free speech detentions reach into Upper Valley

Protesters rally in Lebanon and elsewhere across the country

Protesters rally in Lebanon and elsewhere across the country

ECFiber and operating company trade legal blows as contract renewal talks break down

ECFiber and operating company trade legal blows as contract renewal talks break down

The reports give a detailed description of an arrest, shedding light on what happened — from a police perspective — before, during and after someone is taken into custody.

Dennis claimed it was his department’s “normal practice” not to release reports until cases wind their way through the court system. That can take months, or even a year or more.

On Dec. 20, I went back to Hanover police, requesting the arrest reports under the state’s Right to Know Law. On Jan. 8, I heard from Burrows, the town’s lawyer. Hanover had no intention of turning over the records, claiming “disclosure of any such records would interfere with law enforcement proceedings,” he informed me via email.

I think it’s fair to say Hanover officials assumed that Burrows’ denial of the public records request would be the end of it. They were betting this newspaper wouldn’t want to spend the money to challenge them in Grafton Superior Court.

At the same time, cost was no object for a town as wealthy as Hanover. The Selectboard, then-Town Manager Alex Torpey and Dennis were playing with house money. With Hanover taxpayers footing the bill, they could afford to drag out the case.

Valley News’ attorneys, Bill Chapman and Elizabeth Valez, of Orr and Reno, in Concord, argued that “arrest records” are “governmental records” under New Hampshire law and “subject to disclosure.”

In justices’ words, the Supreme Court has made it clear in recent years that the Right to Know Law is meant to “provide the utmost information to the public about what its government is up to.”

Still, Hanover officials dug in. “We were looking for clarity because the law here is not well defined,” said Selectboard Chairman Carey Callaghan at the board’s most recent meeting on Sept. 9. That night the board voted not to appeal the judge’s decision to the Supreme Court.

To buy the town an additional week in releasing the reports, Burrows waited until 11 p.m. on Monday — an hour before the Supreme Court filing deadline — before releasing the 34 pages.

The reports didn’t reveal any smoking guns. They confirmed, however, that Hanover cops behaved as an extension of the college’s security apparatus to help enforce school rules. A couple of students exercising their constitutional rights by sleeping in a tent on the president’s lawn on a Friday night shouldn’t have become a police matter.

Dartmouth tried to make the students out to be threats to campus safety. Within hours of the arrests, Beilock had already gone into damage control mode. She sent out a campus-wide email, claiming Engels and Wade had adopted a 2014 manifesto written by a Dartmouth student group that threatened “physical action,” if their demands weren’t met.

Did the college have credible evidence that the students were armed? (Information that an arrest report would provide.)

Police didn’t find any “contraband” on Wade, and Engel had only a box cutter. This week, Engel told me he had used it to make protest signs, and forgot it was in his pocket.

Dartmouth waited months, until March 1, to let people know that “after discussions with (Wade and Engel), we now understand that they are consistently nonviolent activists,” then-Dean of the College Scott Brown wrote in campus-wide email.

Still, Dartmouth continues to assist the Hanover police prosecutor in the misdemeanor criminal trespass case against Engel and Wade. Both have pleaded not guilty.

Beilock wants to reinforce her stance that Dartmouth has little tolerance for dissent on its campus. What better scare tactic than having students taken away in police cruisers?

But Beilock wasn’t done. Six months later, she green lighted a show of police force that the Upper Valley had rarely, if ever, seen before May 1. Cops in riot gear from across the state snuffed out a brief and peaceful pro-Palestinian demonstration on the Green. Before the night was over, 89 people were arrested for criminal trespass. A majority of the cases remain open.

This week, I asked Hanover police for the arrest reports they had from the May 1 protest.

Stay tuned.

Jim Kenyon can be reached at jkenyon@vnews.com.

Windsor snow globe business fears Trump tariffs

Windsor snow globe business fears Trump tariffs Fill ’er up: New Hampshire considers allowing patrons to pour their own alcohol

Fill ’er up: New Hampshire considers allowing patrons to pour their own alcohol  School Notes: Red Sox honor longtime Thetford Academy educator Ted Peters

School Notes: Red Sox honor longtime Thetford Academy educator Ted Peters